Australian designs law provides valuable protection for distinctive products

07 October 2021

Australia’s registered designs system, which protects the appearance of products, has always been an underutilised tool in the intellectual property portfolio of brand owners and designers. There are many reasons for this – including a lack of awareness of design rights, the need to keep designs secret prior to filing an application and perceived difficulties in enforcement. However, Australia’s registered designs system is undergoing significant change and the future looks bright for brand owners and designers to protect innovative designs.

The Designs Amendment (Advisory Council on Intellectual Property Response) Act 2021 (the Designs Amendment Act) has recently received Royal Assent (as discussed in previous Insight article). Amongst many other changes, most of which will come into effect on 11 March 2022 at the latest, it introduces a 12 month grace period in which designers can publicly disclose their design prior to filing, bringing Australia into line with most foreign jurisdictions.

The test for infringement has also never been interpreted more widely by the courts, offering a greater scope of protection for registered design owners. It has also been government policy for many years to encourage designers to use the registered design system rather than rely on other intellectual property rights, such as copyright. Since 2004, if designers did not seek design protection for their product, they have been left largely without recourse to stop copycat products. This begs the question as to why brand owners and designers are not making more use of the registered designs system in Australia. Given the increasingly accessible and favourable regime, innovators should start planning to take advantage of the system now in order to gain a competitive advantage.

Why have registered designs been underutilised in Australia?

In 2019, the number of designs filed in Australia was about 7,500 compared to around 75,000 trade marks. Given the amount of product innovation taking place in Australia, this figure would be surprising were it not all too familiar. Product designers operate in a highly competitive market and invest significantly in research and development to get an edge over their competitors. Whether it is a new, innovative product or a distinctive packaging design, designers put significant resources into the development, and subsequent marketing, of new items to consumers. Nevertheless, for a long time, registered designs have been the “poor cousin” of intellectual property rights.

There are many reasons why designs have not been utilised to their full advantage in Australia. Most likely, a lack of awareness of the registered designs system has been a significant factor. For those who are aware of the system, it poses a range of challenges including the need to register the design before it is disclosed to the public, perceived poor prospects of successfully suing for infringement and high costs of enforcement which often cannot be justified, particularly where the infringed design is just one product amongst many in a company’s portfolio.

What changes does the Designs Amendment Act introduce?

The Designs Amendment Act introduces the first major changes to the registered designs system since the Designs Act 2003 (Cth) (the 2003 Act) was introduced. Its primary purpose is to implement several recommendations made by the former Advisory Council on Intellectual Property, following concerns about the effectiveness of the registered designs system in Australia.

The key change introduced by the Designs Amendment Act is a 12 month grace period for filing a design application. Currently, if a designer has published their design before they file their design application, the designer will not be able to obtain enforceable design protection in Australia. This is because any use of the design in Australia, or publication of it in a document anywhere in the world (without appropriate confidentiality undertakings in place), would see the design form part of the prior art base against which the design would be assessed during examination. The prior publication of the design would render the design not new and distinctive and, ultimately, incapable of being certified and enforced. Naturally, this has been a major problem for designers who might have accidentally disclosed their design prior to filing an application or been entirely unaware of the need to seek protection before disclosing the design.

The introduction of the grace period will allow designers to file a design application up to 12 months from the disclosure of the design. The applicant for the design will be permitted to rely on the grace period where the original disclosure of the design was by the designer/s, an employer or successor in title, an authorised party (such as a marketing company) or even an unauthorised party (for example, if the design has been stolen). Importantly, publication by the Registrar of Designs or design offices overseas will not allow an applicant to rely on the grace period.

This change will provide designers with more flexibility in the design process and is also likely to be more cost effective. Designers will now be able to work more freely with third parties on their designs without the need to be as concerned that those disclosures will invalidate their designs. They will be able to more easily test their designs with potential customers and make improvements prior to launch. In many instances, designers will also likely be able to bring their product to market and get a sense of the commercial success of the product before deciding whether to seek design protection. Clothing designers, for example, have dozens of designs every year in respect of which they could seek protection. This system will allow them to identify the designs which have been most successful and are likely to be copied by competitors and seek design protection only for those products if it is too onerous or costly to seek protection for every new design.

Importantly, this new right for designers will be balanced by introducing an infringement exemption that will protect third parties who infringe a design before the priority date of the registration. Third parties who begin using, making, importing or selling products which are substantially similar in overall impression to the registered design during the grace period (i.e. without knowing that the designer intends to seek design protection) will not infringe the registered design.

Whilst there may still be designers for whom best practice will involve seeking designs protection before disclosing the design to any third party, it is likely that many designers will seek to reap the benefits of the grace period to improve their product design process, test products prior to commercialisation and engage with the registered designs system in a more selective way to the advantage of their business. This change also brings Australia into line with many foreign jurisdictions, including the EU and the United States, where a grace period has been a feature of the designs system for years.

How are the courts currently approaching the assessment of infringement?

It is possible that many designers have opted not to seek design protection due to a perception that the rights provided by a registered design are too narrow. Largely, this stems from a belief that a copycat product needs to be virtually identical to the registered design in order for infringement to be found. However, this is not the case.

Under the former Designs Act 1906 (Cth) (1906 Act), the test for infringement was that the alleged infringing product needed to be an obvious or fraudulent imitation of the registered design. In practice, products needed to be bordering on identical in order for infringement to be found. This meant that a designer had very low prospects of success if there were any meaningful differences between the design and the alleged infringement, even if the latter was clearly a copycat product.

The test for infringement was amended in the 2003 Act, to whether the allegedly infringing product was identical or “substantially similar in overall impression”[1] to the registered design. The removal of the “imitation” requirement gave the courts greater scope to find infringement. Whilst a range of factors are set out in the 2003 Act[2] to guide IP Australia’s Examiners and the courts when assessing this concept (including the state of the prior art base, the weight to be given to certain features and the designer’s freedom to innovate), the “overall impression” test provided substantially more scope for design owners to succeed in their infringement cases.

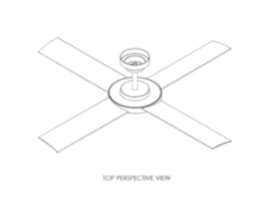

Design infringement cases do not come before the courts with great frequency, likely for many of the reasons we have mentioned including uncertainty about the prospects of success and the high cost of enforcement. The benefits of the broader infringement test for design owners was highlighted in the case of Hunter Pacific International Pty Ltd v Martec Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 796 (Hunter). The Hunter case involved the alleged infringement of Hunter’s registered design for a “ceiling fan hub”. An image of Hunter’s registered design is shown below alongside Martec’s infringing product, noting that the Statement of Newness and Distinctiveness indicated that the shape and configuration of the fan blades as well as the number of blades were to be disregarded.

|  | |

Hunter Pacific's registered design | Martec's infringing design |

His Honour Nicholas J, who presided over the case, noted that there were “a number of obvious differences in shape and configuration” between Hunter’s registered design and Martec’s product. In particular, the registered design did not include a lower canopy and the upper hubs were differently configured. Under the 1906 Act, this would almost certainly have seen Hunter’s infringement action fail, however, Nicholas J held that, despite these differences, there were significant and eye-catching similarities that created an overall impression of substantial similarity. In reaching that conclusion, Nicholas J undertook a a detailed comparison of the products guided by factors set out in section 19 of the 2003 Act. Importantly and favourably to the design owner, the factors require more weight be given to the similarities between the designs than the differences. This factor played a significant role in Hunter successfully establishing infringement. Nicholas J’s review of the prior art base also led His Honour to decide that there was sufficient freedom to innovate in relation to ceiling fan hubs, meaning that it should have been possible for Martec to produce a design which was sufficiently different to the registered design.

Decisions like the Hunter case should provide registered design owners with comfort that there is now greater scope under the 2003 Act to succeed in infringement actions, even where there may be notable differences between the registered design and the alleged infringement.

What options are available to protect intellectual property where a registered design has not been obtained?

A registered design is the easiest and most streamlined way to protect the visual features of a product. Whilst there are other intellectual property rights which may assist to protect the look of a product, these options are quite limited, more difficult to rely upon and likely to be significantly more costly and uncertain than a registered design.

Whilst product shapes and decorative features are, in theory, registrable as trade marks, it can be challenging to establish that those shapes and features are being used “as a trade mark” (i.e. as a badge of origin to indicate trade source), particularly in the absence of lengthy periods of use. This means trade mark protection is generally a very difficult and often unavailable way to protect the visual features of a product.

Furthermore, the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) prevents designers of mass manufactured products from relying on copyright in the underlying artistic works if those products are infringed. The reason for this denial of copyright is to force designers to rely on the registered designs system rather than copyright to protect the visual features of their innovative products. Essentially, the product designer is left without protection if they have failed to register their design (noting that the new grace period discussed above will provide designers with more time to seek such protection). Even in the minority of cases where copyright can be relied upon, it has the added hurdle of establishing that the infringer has (on the balance of probabilities) copied the product, which is not necessary when relying on a registered design. Those wishing to assert copyright can also experience difficulties establishing that they own copyright in the relevant artistic works due to gaps in the business’ records or a failure to secure an assignment of the copyright which, for whatever reason, is unable to be remedied.

This leaves the registered designs system as the cheapest and most streamlined method for designers to secure intellectual property protection for their innovative product designs.

Why register a design in Australia?

Whilst the registered designs system in Australia has had its critics and challenges over the years, it has been and remains the most appropriate intellectual property right to protect the visual features of innovative products. Relying on other intellectual property rights such as trade marks or copyright is fraught with difficulty.

The recent changes to the 2003 Act, which will soon come into force, will make design protection available more widely, including to those who only become aware of registered designs after experiencing some commercial success. The changes will also allow designers the flexibility to test and improve their products before bringing them to market whilst keeping the possibility of design protection alive.

Design owners should get some comfort from cases like Hunter that designs law is now set up to favour them in enforcement proceedings. Whilst it is typically expensive to enforce intellectual property through the courts, the vast majority of cases are able to be resolved without the need to commence proceedings or at an early stage of proceedings, including via mediation. Upon being notified of the existence of a registered design, many competitors will cease their infringing activities in order to avoid incurring significant legal costs. A registered, certified design is a powerful tool in an intellectual property kitbag, and one which assists designers to maintain a crucial competitive advantage in today’s marketplace.

Authors

Consultant

Tags

This publication is introductory in nature. Its content is current at the date of publication. It does not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. You should always obtain legal advice based on your specific circumstances before taking any action relating to matters covered by this publication. Some information may have been obtained from external sources, and we cannot guarantee the accuracy or currency of any such information.