Corporate Collective Investment Vehicles: a new fund structure becomes reality

02 March 2022

A new company structure, the corporate collective investment vehicle (CCIV), is now reality, and will be included in the Corporations Act from 1 July 2022. What should the funds management industry know about the new CCIV structure and what implications will it have for the future regulation of financial services?

Despite a lengthy gestation period which commenced with a worthy recommendation from the Johnson Report in 2009, a new law was passed on 22 February 2022, establishing the company structure known as a “corporate collective investment vehicle” (CCIV).

The creation of the CCIV structure aims to enhance Australia’s funds management industry by introducing a more globally recognisable investment structure; focusing on Australia as a regional financial services hub. The CCIV was born from the concern that offshore investors may perceive the traditional trust-based structure of our domestic managed investment schemes as ‘inappropriate for large-scale funds management’.[1]

The CCIV is therefore an alternative investment vehicle to managed investment schemes, with proponents suggesting that the familiarity of the ‘corporate’ fund structure to many foreign investors, will attract more offshore investment into Australian funds.

The new law will insert a new Chapter 8B in the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act) containing the core provisions outlining the establishment of CCIVs and their operational and regulatory requirements.

Funds management businesses can begin registering their proposed CCIVs with ASIC from 1 July 2022.

What are the characteristics of a CCIV?

A CCIV is an investment vehicle with a corporate structure, having the legal form of a company limited by shares.

To expand on this, and similar to other company structures, a CCIV:

- will be recognisable as a separate legal entity, and can therefore enter into contracts in its own right and deal with its own company shares;

- must have a constitution;

- will have most of the powers, rights, duties and characteristics of a company; and

- will generally be subject to the ordinary company rules under the Corporations Act, unless otherwise specified.[2]

Some key features of this new regime are as follows:

- a single CCIV can act as an ‘umbrella vehicle’, by offering multiple products (ie sub-funds) and investment strategies within the same vehicle. The aim is that each sub-fund will effectively operate as a protected cell for asset and liability purposes;

- the CCIV will have a single corporate director – with that corporate director:

- being an unlisted public company; and

- holding an Australian financial services licence (AFSL) that authorises it to ‘operate the business and conduct the affairs of the CCIV’ (this is a new CCIV-specific AFSL authorisation);

- being an unlisted public company; and

- the CCIV must not have any officers or employees other than the single corporate director (although the single corporate director may have officers and employees of its own);

- the CCIV is exempt from the requirement to hold an ASFL to issue securities in the CCIV. Instead, as mentioned above, the corporate director must hold the relevant authorisation under its AFSL; and

- a CCIV can be either a retail or wholesale CCIV – note however, that just one retail client in a CCIV will make the CCIV a ‘retail CCIV’, which is subject to greater disclosure (ie product disclosure statements (PDS)) and potentially other regulatory obligations, such as the design and distribution obligations.[3]

What is the structure of a CCIV?

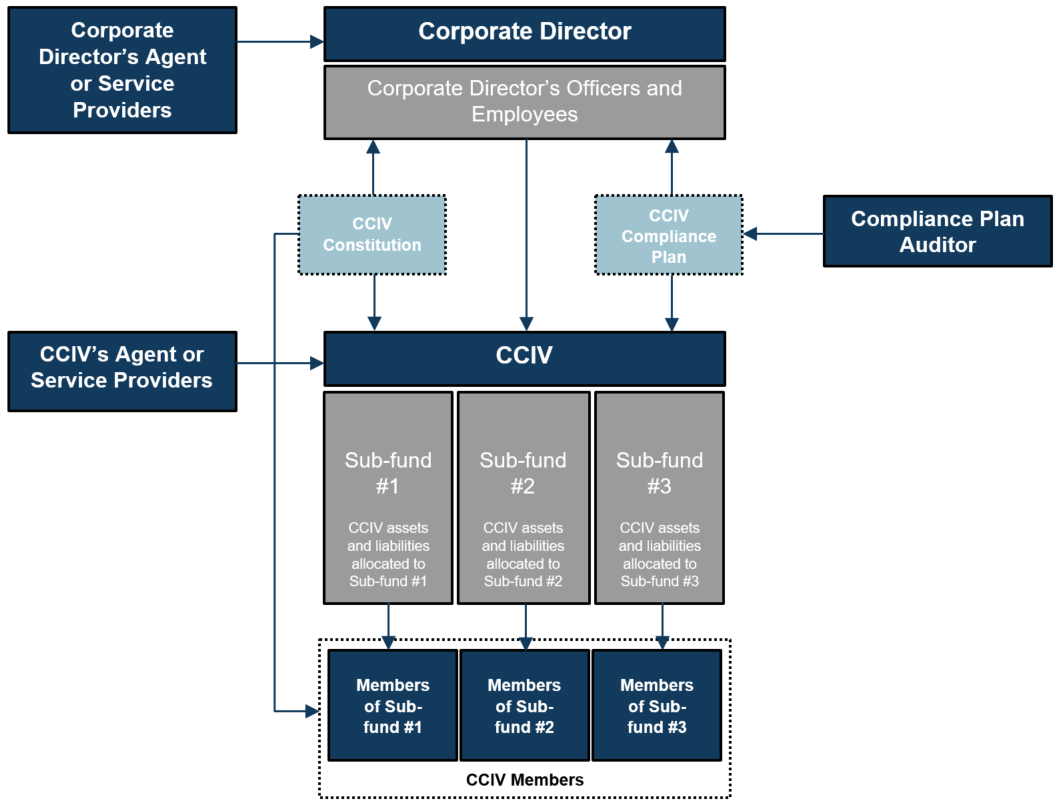

The Explanatory Memorandum to the Corporate Collective Investment Vehicle Framework and Other Measures Bill 2021 (Cth) provides the following diagram, which demonstrates how the new CCIV regulatory framework will operate:[4]

How do you register a CCIV?

A CCIV will be registered with ASIC if it meets certain basic registration requirements, with the key requirements being that it must:

- be a company limited by shares;

- have a constitution that meets prescribed content rules (as is the case for a managed investment scheme);

- have a sole proposed corporate director that is a public company which holds an AFSL authorising it to ‘operate the business and conduct the affairs of the CCIV’; and

- have at least one sub-fund, with each sub-fund having at least one member.[5]

It is important to note that upon registration:

- the CCIV will have a legal personality. Although sub-funds will not have separate legal personality, the new regime effectively has sub-funds operating as separate protected cells (each with assets and liabilities);

- the CCIV must have the expression ‘Corporate Collective Investment Vehicle’ at the end of its name;

- a sub-fund’s name must also adhere to certain naming requirements under the Corporations Act; and

- each registered sub-fund will be given an ‘Australian registered fund number’ (ARFN).[6]

Registration of a subsequent sub-fund is by a standalone process, and any securities issued by the CCIV must be issued in relation to a specific sub-fund.[7]

Unlike some other company structures, a CCIV cannot change company type once registered as a CCIV.[8]

What are the expectations of the single corporate director?

A CCIV’s single corporate director:

- is required to obtain the newly introduced AFSL authorisation to ‘operate the business and conduct the affairs of the CCIV’ – a single AFSL may cover operating the business and conducting the affairs of more than one CCIV;

- must ‘operate the business and conduct the affairs of the CCIV’ in accordance with the conditions of its AFSL authorisation, the CCIV’s constitution, and the Corporations Act, which includes general directors duties such as the duty to act honestly and in members’ best interests, as well as CCIV-specific directors duties (which apply to retail and wholesale CCIVs separately). For example, an additional retail-specific director’s duty would include ensuring that the assets of a CCIV’s sub‑fund are valued at regular intervals; and

- is generally responsible for the conduct of the CCIV, and will therefore be subject to criminal and/or civil penalty provisions for its breaches of its ASFL or the relevant law – as the CCIV has no other officers or employees aside from the single corporate director, the CCIV will itself not be responsible for breaches in its name.[9]

What are the implications for financial services licencing and disclosure?

The new regime will amend the Chapter 7 licencing provisions of the Corporations Act, relating to assigning responsibility for licensing, conduct and disclosure.

Financial services licencing

As mentioned above, a single corporate director operating a CCIV can only ‘operate the business and conduct the affairs of the CCIV’ if it is authorised to provide this financial service under its AFSL. As such, this new financial service will be added to the list available under section 766A of the Corporations Act, alongside ‘providing financial product advice’ and ‘dealing in a financial product’.

However, a corporate director will not be authorised to issue securities under this new AFSL authorisation. This is because the CCIV itself will issue the securities pursuant to an exemption to holding an AFSL available under the Corporations Act (which is specific to CCIVs issuing securities).

Other entities that provide financial services in relation to or on behalf of a CCIV (for example, an agent of a CCIV), may also require an AFSL in relation to those services.[10]

Disclosure

A CCIV (rather than its corporate director) is generally responsible for giving retail clients a PDS relating to the relevant sub-fund, prior to issuing the retail client securities (eg shares and debentures) in the relevant sub-fund. The sub-fund’s PDS may include further information in relation to the CCIV as a whole. This differs from the requirement for a retail client to be issued with a prospectus for the issue of securities under Part 6D.2 of the Corporations Act. A CCIV’s PDS is generally subject to the same content requirements that ordinarily apply to PDSs for other financial products. This approach is aimed at ensuring consistency with the disclosure arrangements that apply to registered schemes.[11] The Regulations also create a category of “simple sub-fund products” which are intended to be similar to simple managed investment schemes – meaning that the simple PDS regime will apply to such sub-funds.

Other important legislative changes

The new law proposes to make consequential amendments to other legislation to support the implementation of CCIVs, such as amendments to the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth), Personal Property Securities Act 2009 (Cth), and tax legislation.

The ASX is also consulting on proposed changes to the ASX Listing Rules and ASX Operating Rules to allow for the listing of CCIVs and sub-funds.

Amendments to tax legislation will ensure that the tax treatment of CCIVs aligns with the existing treatment of attribution managed investment trusts (AMITs), providing investors with the benefits of flow-through taxation (subject to a sub-fund not tripping up the traditional public trading trust test that applies to managed investment schemes).[12]

Was it worth the wait?

One of the key objectives for introducing the CCIV regime has been the desire to increase the competitiveness of Australia’s funds management industry by providing greater choice and an internationally recognisable fund structure. Whether this becomes reality remains to be seen as there are several issues which remain to be addressed at a later point.

For example, the proposed regime has yet to articulate how, if at all, existing funds can transition to the new CCIV regime without creating unintended tax consequences. The absence of any stamp duty relief from the States and Territories will likely act as a disincentive for existing managers looking to transition their funds into a CCIV structure. Moreover the tax treatment for sub-funds of a CCIV that do not meet the conditions to qualify as an AMIT may pose some issues for the CCIV in terms of parity of tax treatment compared to managed investment schemes.

Given these considerations, the appropriateness of the new CCIV structure for new and existing Australian-domiciled funds should be determined on a case by case basis.

[1] See the Explanatory Memorandum to the Corporate Collective Investment Vehicle Framework and Other Measures Bill 2021 (Cth) (Bill) (Explanatory Memorandum), [1.9], [1.14], and [1.17]; and Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act), s 1221(a).

[2] Corporations Act, ss 1223 and 1223A; and Explanatory Memorandum, [1.19], [1.24], and [1.40].

[3] Corporations Act, ss 1222D(1), 1224, 1224A, 1224B, 1224F, and 1222J – 1222M; and Explanatory Memorandum, [1.26], [1.31]-[1.35], [1.41]-[1.44], [1.90], and [9.9].

[4] Explanatory Memorandum, [1.96] Diagram 1.1 Regulatory framework for a CCIV.

[5] Corporations Act, ss 1222, 1222A, and 1222Q(2).

[6] Corporations Act, ss 1222E(2), 1222S(3), and 1222Q(2); and Explanatory Memorandum, [1.38].

[7] Corporations Act, ss 1222(d) and (e), and 1222S(2); and Explanatory Memorandum, [1.29], [1.37], and [1.73].

[8] Corporations Act, s 1222P.

[9] Corporations Act, ss 1224D, 1224J, and 1222P; and Explanatory Memorandum, [1.45], [1.60], and [9.21].

[10] Explanatory Memorandum, [1.28], and [9.17].

[11] Explanatory Memorandum, [9.7], and [9.29]-[9.33].

[12] Explanatory Memorandum, [1.2], and [1.15].

Authors

Partner

Associate

Tags

This publication is introductory in nature. Its content is current at the date of publication. It does not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. You should always obtain legal advice based on your specific circumstances before taking any action relating to matters covered by this publication. Some information may have been obtained from external sources, and we cannot guarantee the accuracy or currency of any such information.

Key Contact

Other Contacts

Senior Associate (Admitted in Belgium, not admitted in Australia)