Do new draft EPBC National Environmental Standards ignore Independent Review of EPBC Act recommendations?

26 May 2021

The ambition of the Final Report of the Independent Review of the EPBC Act to devolve the process-related assessment of projects (which impact on matters of national significance) to state and territory governments - allowing the Commonwealth to ‘lift its head’ to deal with the more strategic environmental challenges, data collection, performance measurement and enforcement - is a worthy one.

However, strong political leadership will be necessary to ensure parochial state-based economic drivers do not impede holistic national environmental and cultural heritage protection.

The Final Report by Professor Graeme Samuel (released in January 2021), together with the Bill currently before Parliament, signify an important step in the rejuvenation of Australia’s national environmental laws. However, as flagged in our earlier article, important questions remain surrounding how, and to what extent, Professor Samuel’s recommendations will be implemented.

The May 2021 Federal budget allocated a comparatively meagre sum of $29.3 million over the following four years as an initial response to the Independent Review of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (EPBC Act). Of this, $17.1 million is to be allocated to maintain timely assessments and approvals in the transition period. Additional investment will be needed over time to achieve Professor Samuels goals.

EPBC Act Review: Final Report released

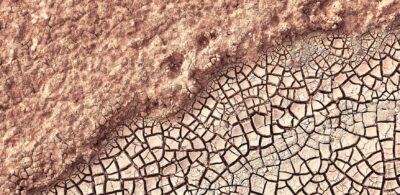

Building on the preliminary views outlined in the Interim Report, the findings of the Final Report were bleak. Its key message, and one repeated throughout the Report, was that:

“Australia’s natural environment and iconic places are in an overall state of decline and are under increasing threat. The environment is not sufficiently resilient to withstand current, emerging or future threats, including climate change. The environmental trajectory is currently unsustainable.”

The Final Report is clear-headed and deliberate in its messaging, and establishes a regulatory pathway for the Federal Government.

To address these issues, and ensure the Australia’s future sustainability, the Final Report makes 38 recommendations for reform. These reforms are largely consistent with the recommendations of Professor Samuels’ Interim Report.

Regulatory pathway

To ensure that the recommendations are delivered in a coordinated manner, they have been grouped into three tranches:

- Priority Reforms;

- Enabling Reforms; and

- Final Reforms.

Tranche One: Priority Reforms

The first tranche of reforms are focused on three key changes:

- the creation of enforceable National Environmental Standards (Standards);

- the appointment of an Environment Assurance Commissioner (Commissioner) to oversee the implementation of and compliance with the Standards; and

- the inclusion of Indigenous knowledge in all environmental decision making.

In response to the urgency of the tranche one reforms, on 25 February 2021, the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Amendment (Standards and Assurance) Bill 2021 (Bill) was introduced into Federal Parliament.

Standards

Historically, the states and territories have enjoyed considerable discretion for environmental decision-making. This has led to a project-by-project rather than a holistic, outcomes-based approach to decision-making.

To overcome this issue, the Final Report strives to achieve much greater clarity by proposing Standards which set particular requirements for decision-makers in relation to:

- Matters of National Environmental Significance (MNES);

- Indigenous engagement and participation in decision-making;

- compliance and enforcement; and

- data and information.

Commissioner

To support their implementation, the Commissioner will be responsible for overseeing the Standards. The Bill contemplates that the Commissioner will have the ability to audit and monitor the performance of the states and territories to determine whether they are adhering to the Standards.

However, criticism has already been levelled at the proposed environmental auditor. Under the Bill, the Commissioner’s powers of audit are effectively limited to the preparation of reports. If states or territories violate the Standards, it is unclear whether the Commissioner will have the power to hold the them to account.

Even with the appropriate powers, with just $9 million allocated over the course of four years to the Commissioner enforcement activity may be selective.

By way of comparison, although not necessarily all appropriated from the State, the operating expenditure budget for the NSW Environment Protection Authority for the 21/22 financial year is $213.6 million.

Indigenous Knowledge

The Final Report is critical of the fact that the EPBC Act fails to respect and harness the knowledge of Indigenous Australians to better inform how the environment is managed.

Despite the involvement of Indigenous Australians in land and sea protection around the country this is not reflected in the EPBC Act, which does not incorporate the rights of Indigenous Australians in the decision-making process. As a consequence, this has caused Australia to lag in its implementation on it key international commitments relating to Indigenous peoples’ rights.

For example, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) emphasises that it is a right of Indigenous peoples to participate in the decision-making process for matters that affect them.

The Final Report finds that the current EPBC Act overtly prioritises the views of Western science, at the expense of the knowledge and values held by Indigenous communities. To enhance the inclusion of Indigenous Australians in environmental decision-making, the Final Report recommends immediate reform to realign the EPBC Act with Australia’s international commitment to the rights of Indigenous peoples. By doing so, it is hoped that Indigenous knowledge will be repositioned alongside Western science in the decision-making hierarchy.

Tranche Two: Enabling Reforms

The second tranche of reforms are essentially the ‘enabling’ reforms. Over the next 12 months, to successfully deliver the recommendations of the Final Report, comprehensive amendments to the EPBC Act are required. To achieve this, the Final Report recommends that Parts 3 to 10 of the Act be completely overhauled to support the effective integration of the Standards into environmental decision making.

This recommendation comes in response to the criticism that decision making requirements, especially in relation to MNES, are buried within voluminous statutory documents and unenforceable guidelines. Hence, the intent of the ‘enabling’ reforms is to enable the Standards to be more efficiently applied to decision-making.

The Tranche Two reforms also propose the introduction of limited merits review for development approval decisions available to proponents and others with standing. This merit appeal right would be restricted to the material available at the time of the original decision. In other words, a merits review ‘on the papers’.

Presently, the ‘standing’ rules enable third parties to bring judicial review appeals to challenge the validity of decisions made under the EPBC Act. Eschewing the notion of environmental ‘lawfare’, the Final Report is firm in stating that the current standing rules will not be changed.

However, in an effort to limit baseless and vexatious litigation, the Final Report suggests potential litigants should be required to provide the written advice of senior counsel to demonstrate that their claim has a reasonable prospect for success.

On one view, this is a relatively low bar to meet. On another view, this possibly raises access to justice concerns, where concerned parties are required to find the funds to obtain the opinion of senior counsel before ‘passing first base’ on a merits review.

Tranche Three: Final Reforms

The third tranche of reforms represents the finale to the legislative overhaul initiated in February 2021. It is anticipated that the redrafting of the EPBC Act will completed by 2022.

While the details surrounding Tranche Three are limited, the Report states that the final reform will be aimed at restructuring the EPBC Act to simplify its operation.

Draft Standards

In early February 2021, an incomplete version of the proposed Standards was informally released to the public. At the time, it was unclear whether this version of the Standards would be implemented, however the general consensus was that they fell well short of those recommended by Professor Samuel.

This led to widespread criticism by environmental groups, such as the Australian Conservation Foundation, which accused the Government of “simply replicat[ing] existing problems in the EPBC Act”.

The Federal Government has now released the final draft of the new Standards, with the qualification that the “Standards will initially reflect the existing requirements of the EPBC Act”. As a result, the new Standards do not reflect many of the recommendations included in the Final Report. For instance, the need for decisions to “reflect the principle of non-regression”, is absent from the new Standards.

The principle of non-regression requires environmental norms which have already been adopted by countries not to be revised if the overall effect of the revision would be regressive. It is based on the idea that the diminution of laws to protect the environment would contradict the principle of inter-generational equity. By excluding this principle, it would enable states and territories to go back on their environmental progress by allowing them to make retrograde decisions and policy choices.

Other elements of the draft Standards which appear contrary to the recommendations of the Final Report include the absence of requirements on decision makers to ensure that:

- their decisions reflect relevant conservation practices;

- they have considered the ‘best available information’ when making decisions on MNES;

- decisions support rights of indigenous peoples to practice customary activities and traditions; and

- decisions take into account both individual and cumulative impacts.

The biggest criticism, however, is the fact that during the first two years of their operation, the new Standards will not be disallowable by Parliament. This means that the Standards could be in place for two years, before the Standards recommended by Professor Samuel’s are introduced.

While a review of the Standards must be undertaken within two years of their commencement, there is no requirement in the Bill mandating that the Standards be varied. As a result, the Standards could operate indefinitely without ever being subject to Parliamentary oversight and therefore continue to eschew the recommendations made by Professor Samuel.

Concluding observations

With the Bill referred to the Senate Standing Committees on Environment and Communications for inquiry, the first round of priority reforms is unlikely to come into effect until late-2021. However, they are important as the passage of the first Bill of reforms will set an important tone for subsequent legislative changes.

Authors

Head of Gender Equality

Associate

Tags

This publication is introductory in nature. Its content is current at the date of publication. It does not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. You should always obtain legal advice based on your specific circumstances before taking any action relating to matters covered by this publication. Some information may have been obtained from external sources, and we cannot guarantee the accuracy or currency of any such information.

Key Contact

Head of Environment and Planning