Is this the end of the 5% tolerance in off-the-plan developments?

22 September 2021

A recent Supreme Court decision has caused some unease in the industry, as it found that a reduction in size of a lot, of less than 5%, “materially affected” the lot in question, entitling the purchaser to rescind the off-the-plan contract. What does this mean for the future of the 5% tolerance?

It has been commonly accepted across the market that a variation of 5% or less in the size of a lot does not materially affect a lot, so it has been interesting to unpack the findings of Burger & Ors v Longboat Holdings Group2 Pty Ltd [2021] VSC 469 (Burger v Longboat), which found a variation of less than 5% did have material affect.

As we discuss below, this is not the end of the 5% market tolerance, but a timely reminder that the practical implications of changes to a plan of subdivision need to be carefully considered.

Development of the 5% market tolerance

The 5% market tolerance was developed through previous Victorian judgments[1] which considered this percentage a ‘material cut off’ for residential lots.

The contract of sale in Burger v Longboat had a special condition which stated that the ‘purchaser acknowledges and agrees that an amendment made to the Plan which alters the area of the property by 5% or less will not be regarded as an amendment which materially affects the property.’[2] This type of provision is standard across almost all off-the-plan contracts.

However such a provision does not negate the test of whether a change “materially affects” the lot, as parties cannot seek to contract out of purchasers’ rights under the Act.

What materially affects a lot?

To determine whether a change materially affects a lot, consideration must be given to whether the change will affect the ‘bundle of rights’ of the purchaser to a ‘important or significant degree’.[3] There is no requirement the amendment is detrimental or adverse to the purchaser.[4]

Importantly, the question of materiality is a factual question that must be answered in the context of the particular development, as opposed to a checklist of factors or set list of metrics, like a rigid 5% change in size.

The cautionary tale of Burger v Longboat

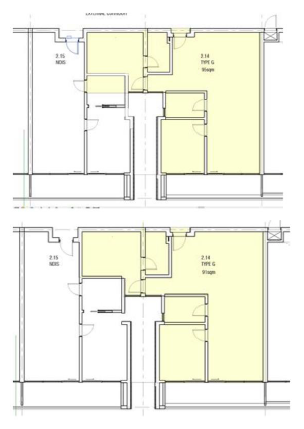

Burger v Longboat considered changes in size of two separate lots in an off-the-plan development, which had similar boundaries, size and shape.

Between the contract of sale plan (Contract Plan) and amended plan (Amended Plan), there was a total reduction in size from 95m2 to 91m2 – a change of slightly less than 5% of the size of the property.

The primary change to the lots was in the main bedroom. The difference between the two plans is helpfully illustrated in the below diagram. The first diagram illustrates in yellow the size of the lot in the Contract Plan over the top of the Amended Plan. The second diagram illustrates in yellow the area of the Amended Plan.

Irrespective of the reduction in size being less than 5%, the Court considered the change to have materially affected the lots.

The Court placed significant weight on the reduction in size being primarily to the master bedroom, commenting that a reduction in size of almost 4m2 (which effectively reduced the size of the master bedroom by a quarter), ‘to a master bedroom that could hardly be described as palatial prior to the change, is clearly material’.[5]

Additionally, the Court agreed with the purchaser’s argument that the change is exacerbated by the creation of the alcove which created unusable space, making it very difficult for typical bedroom furniture to be manoeuvred into the room.[6] The changes also impacted the ‘attractiveness of the room’.[7]

These changes were coupled with a reduction in the size of the light court outside the master bedroom.[8] Despite providing no expert opinion of the light flow, and the vendor disputing that the size of the light court between the plans had changed, the Court was satisfied the change had materially affected the lots. The Court acknowledged while the change in the light court in isolation may not have been material, in combination with the changes to the master bedroom, the flow of light in to the bedroom was sufficiently impacted.

This case should not be taken to remove the 5% market tolerance. Rather it is a cautionary tale of failing to consider the practical impacts on purchasers in reducing the size of lots. If the reduction in size had a lesser impact on the useability and utility of the lot, the 5% or less margin may have been a sufficient marker to assess the material effect on the lot.

Other changes

The off-the-plan development the subject of Burger v Longboat also had other changes which impacted the purchasers.

Between the Contract Plan and the Amended Plan, a section of common property became a Maribyrnong City Council Reserve (MCC Reserve). Consideration was given to the impact on lot owners no longer holding proprietary or exclusive rights to the property, even if it was common property. The Court determined that the ‘lack of exclusivity alone is a change which materially affects [the] Lots’. [9]

The Amended Plan also created common property 2, reallocating some common property to a new owners corporation which was then only accessible to owners of a portion of the lots in the development, which did not include the lots in question. The Court decided that while the area of land was relatively small, the ‘loss of use of a terrace or the ability to create a terrace, is not insignificant’,[10] as they lose any rights in relation to that land.

Changes to the lot’s allocated car parks were also made in the Amended Plan, decreasing the size and changing the location of the car parks. Interestingly, the Court found that these changes did not materially impact the lots despite the size of one of the car parks being reduced by 11%. It appears that central to this finding was that the change did not impact the utility of the car park or result in certain cars being unable to access the car park.[11] Therefore, despite the finding, caution should still be taken to consider whether changes to any car parks materially affect lots.

Key Takeaways

This case highlights the importance of developers having progressed plans prior to going to market to reduce the risk of changes having material effect on lots which provide rescission rights to purchasers. In circumstances where changes are unavoidable, developers should be aware of the potential rescission risks and how this may impact on financial arrangements.

[1] See Birch v Robek [2014] VCC 68; Buckley v Drk (Unreported, Supreme Court of Victoria, Teague J, 30 April 1993).

[2] Burger [22].

[3] Burger [49], citing Harris v K7@Surry Hills Pty Ltd [2019] VSC 551, [98].

[4] Burger [49], citing Harris v K7@Surry Hills Pty Ltd [2019] VSC 551, [98].

[5] Burger [79].

[6] Burger [80].

[7] Burge, [61].

[8] Burger [90].

[9] Burger [126]-[127].

[10] Burger [140].

[11] Burger [169]-[171].

Authors

Partner

Associate

Tags

This publication is introductory in nature. Its content is current at the date of publication. It does not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. You should always obtain legal advice based on your specific circumstances before taking any action relating to matters covered by this publication. Some information may have been obtained from external sources, and we cannot guarantee the accuracy or currency of any such information.