Sweeping reforms to Australia’s merger control rules announced

11 April 2024

The Australian Government has announced sweeping reforms to Australia’s merger rules that will commence in January 2026.

Australia will replace its voluntary, non-suspensory regime with a mandatory and suspensory system, subject to forthcoming economic and market share thresholds. The new rules are largely consistent with other comparable jurisdictions’ regimes. The changes represent a reasonable balance between the ACCC’s proposals and the Australian business community’s responses to the Treasury’s consultation process.

There are some limited changes to the legal test, but no fundamental changes as to the substantive assessment of mergers. The major changes will be procedural, and our view is that more potential acquisitions will be subject to notification obligations and suspension, even where there are no or limited competition concerns. Much depends on how effectively the economic and market share thresholds are set. The Treasury will consult on draft legislation, including notification thresholds, in 2024.

Key reforms

Australia’s merger control system will change in the following ways:

- Nature of regime will change. From January 2026, a single mandatory and suspensory merger control system will replace the ability to approach the Federal Court for a negative declaration, informal merger review process and merger authorisation process. The ACCC will be responsible for a single merger control pathway, replacing the current three voluntary pathways and will be the only first instance decision-maker.

- Legal test and substantive assessment. A merger may proceed unless the ACCC reasonably believes it is likely to substantially lessen competition, including if it ‘creates, strengthens, or entrenches substantial market power’. Further, to respond to concerns regarding serial or creeping acquisitions and ‘roll up’ strategies, the cumulative effect of all mergers within the previous three years by the merger parties may be considered as part of the assessment of the notified merger, whether or not those mergers were themselves individually notifiable.

- Notification thresholds. Notification will be required for transactions that exceed certain economic and market share thresholds, which have not yet been identified. A person acquiring ‘control’ of a business or assets will be required to notify the ACCC of a merger that meets the thresholds. All mergers within the previous three years by the acquirer or the target will be aggregated for the purposes of assessing whether a new merger meets the notification thresholds, irrespective of whether those earlier mergers were themselves individually notifiable. The Treasury will consult on the thresholds in 2024.

- Penalties / consequences of contravention. A failure to notify a notifiable merger or closing prior to ACCC approval will be subject to substantial penalties for merger parties and executives or officers. In addition, any illegally implemented merger, or contract, arrangement or understanding related to it, will be void.

- Fees. Merger reviews will be subject to fees in the likely range of A$50,000-A$100,000. There will be additional fees for Australian Competition Tribunal (Tribunal) review. An exemption will be available for small businesses.

- Transparency and precedent. The ACCC will be required to maintain a public register including details of notified mergers and the ACCC’s reasons for its determinations.

- Appeal rights. The Tribunal will be the only route to review ACCC decisions, on a limited merits basis, subject to material placed before the ACCC. The Tribunal may seek clarifying information, and the Tribunal may allow the parties to present new information or evidence which was not in existence at the time of the ACCC’s determination. A fast-track review by the Tribunal may be sought, based only on the material before the ACCC, and the Tribunal would be bound by the findings of fact made by the ACCC.

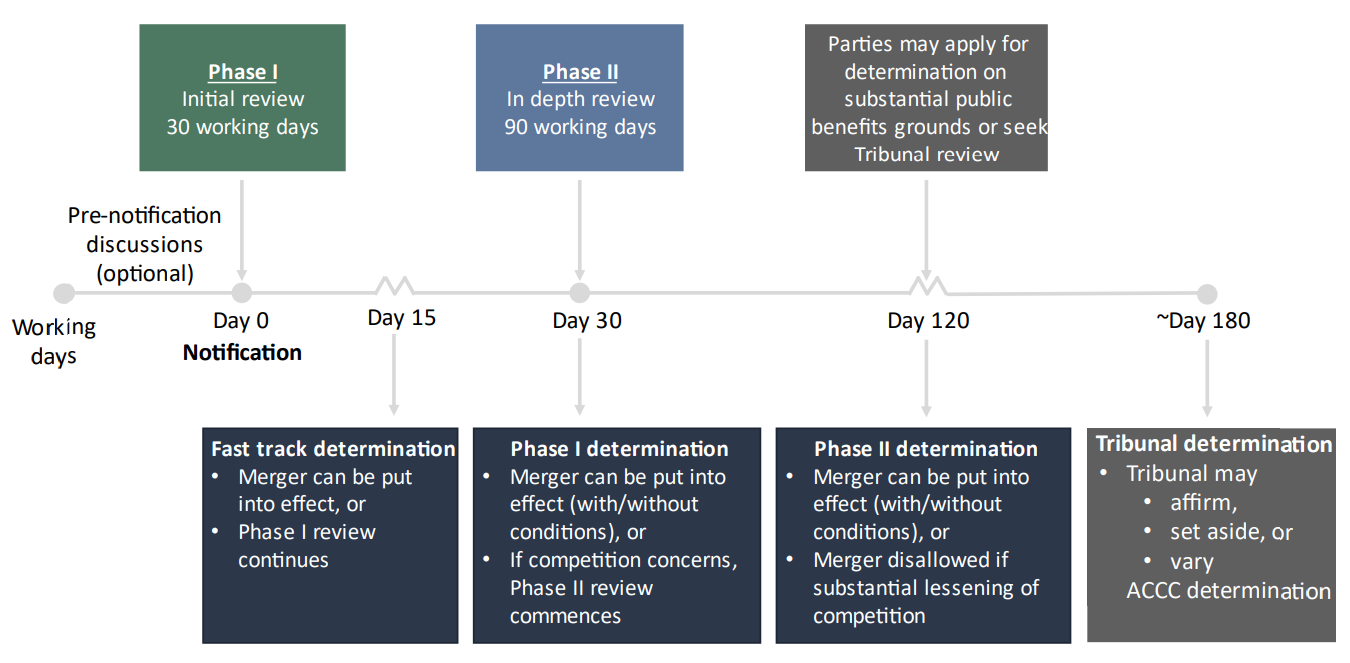

The new indicative review timelines and processes are as follows:

- ACCC. Indicative timeframes of 30 working days for ‘Phase I’ reviews and 90 working days for ‘Phase II’ reviews, with fast-track determinations after 15 working days if no competition concerns are identified. The Phase I review period would commence upon receipt by the ACCC of a complete notification. The ACCC will consult on the form of notification to be required in 2025. If the ACCC does not make a determination within those time periods, the merger is deemed cleared. Merger parties will be able to engage in prenotification discussions with the ACCC. The Treasury will consult on the rules as to how the statutory ‘clock’ can start and stop and other procedural safeguards in 2024. Following a Phase II rejection, merger parties may seek approval from the ACCC if the ACCC is satisfied the merger would be likely to result in a substantial benefit to the public which outweighs the anticompetitive detriment of the merger. That will replace the existing merger authorisation process (with a 50-working day timeline).

- Tribunal. The Tribunal’s review will be subject to a time limit of 90 calendar days (approximately 60 working days), which could be extended by a further 90 calendar days where necessary, as it is currently. If a fast-track review by the Tribunal is sought, the Tribunal’s review will be subject to a time limit of 60 calendar days (approximately 40 working days), with no option for extension.

The Treasury will set the merger review timelines following consultation in 2024. The initial timelines, as published by the Treasury, are set out in diagrammatic form below:

Source: The Australian Government, the Treasury, Competition Review, Merger Reform: A Faster, Stronger and Simpler System for a More Competitive Economy, 10 April 2024.

Implications

The new rules are largely consistent with other comparable jurisdictions’ regimes and represent a reasonable balance between the ACCC’s proposals and the Australian business community’s responses. The ACCC has welcomed the new rules, as have some business community stakeholders (noting the requirement for further consultation).

Our views on the likely implications are as follows:

1. Limited changes to the legal test, and no fundamental changes in the substantive assessment of mergers

The addition of the words ‘creates, strengthens, or entrenches substantial market power’ to the current substantial lessening of competition test will not materially change the way in which the ACCC analyses mergers. There is a risk that the addition of this language will embolden the ACCC to increase its reliance on more fringe conglomerate or ‘ecosystem’ theories of harm, but it already has the power to investigate a variety of concentrative transactions by large companies, including transactions where large companies extend their operations into adjacent products or services.

The Government rejected a radical proposal to reverse the burden of proof in the legal test. The ACCC had proposed to shift the burden to prove that a merger is not likely to substantially lessen competition onto merger parties. That proposal would have placed Australia out-of-step with international peers. The Treasury heard from stakeholders that this could introduce systematic bias, increase the number of rejected mergers every year, and effectively introduce a presumptive ‘ban’ on mergers.

The ACCC is concerned by serial acquisitions or ‘roll up’ strategies, and has made two proposals to counter strategic behaviour in this area. All ‘mergers’ within the previous three years by the merger parties may be considered as part of the review of a notifiable merger and will be aggregated for the purpose of assessing whether a merger meets the notification thresholds, irrespective of whether those mergers were themselves individually notifiable. Those changes are likely to affect the strategies of serial acquirers (like private equity players) and may also affect exiting founders (for example of technology or startup businesses). The ACCC can already consider, and develop enforcement strategies to combat, the anticompetitive effects of previous non-notified acquisitions. It has done so recently in Woolworths/Petstock, where Petstock was required to make a number of divestments to address local concentrations created by previous non-notified transactions.

As these tools are already available to the ACCC, we do not anticipate any significant change in substantive review focus. However, dealmakers with these strategies (on both the buy-side and sell-side) will need to accept that more potential acquisitions will be subject to ACCC conditions and the proposed suspension obligations, even where there are no or limited competition concerns. Some bidders, whose overlap with a target has increased over time through a series of acquisitions, may face more complex or longer reviews arising from their recent transaction histories.

2. If thresholds are effectively set, the new rules could deliver greater timing and process certainty

The Treasury anticipates that the thresholds will be set such that the overall volume of notifications to the ACCC will be similar to current volumes (approximately 300 per year). We anticipate that substantially more mergers will be subject to notification obligations and suspension after the new rules commence. Much will depend on how effectively the economic and market share thresholds are set, and draft legislation, including the merger notification thresholds and the definition of a notifiable merger, will be forthcoming in 2024.

The rejection of another radical proposal to give the ACCC a power to ‘call in’ transactions that fall under the economic and market share thresholds, which would have reduced certainty for dealmakers and placed Australia out-of-step with international analogues, is welcome. That power would have undermined the main benefit of a mandatory regime which is certainty as to when a transaction requires notification.

We note that merger parties are encouraged to make informal contacts with the ACCC in respect of their notifications pre-filing. Again, the greater timing certainty provided by statutory timetables is welcome, but it would be undermined if the ACCC engaged in excessively long ‘prenotification’ contacts before a filing is formally accepted and the statutory clock starts.

For smaller deals, or deals with no or very limited overlap, which would not likely have been filed with the ACCC under the old rules but would be caught by the new notification thresholds, the new rules inevitably imply delays of at least a month (to account for prenotification and even a fast-track review), increasing transaction costs, deal risks and complexity in competitive sales processes.

3. Increased precedent and more transparency is welcome

Publication of detailed reasons for decisions would bring the ACCC into line with its international peers and would be a welcome development. At present, the ACCC’s reasoning for, and analysis in relation to, its merger decisions is often opaque – both for parties and non-parties. Publication of detailed reasons would allow interested parties and practitioners to better understand the ACCC’s analysis and allow a more useful body of precedent to develop. In the last 12 months, the ACCC published only six statements of issues and a smaller number of public competition assessments. It only reviews publicly between 20-30 mergers, and some public register entries in relation to those deals are cursory.

We anticipate that the ACCC will face a significantly increased resourcing burden from the larger numbers of merger reviews, and will need to take on a range of new resources to draft and publish decisions and process guidelines that contain sufficient detail for merging parties.

4. Limited merits review erodes a material procedural safeguard against ineffective decision-making

The new rules remove the option to seek a negative declaration from the Federal Court and limit appeal rights to limited merits review before the Tribunal. That erodes an important safeguard against over-enforcement and poor decision-making. Full merits review would have been fairer and improved the process.

In a limited merits review, merger parties are placed at a disadvantage because they are unable to properly test third parties’ submissions and evidence, as cross-examination opportunities and the ability to submit new evidence that was not before the ACCC are limited. This is an important differential between the rights of merger parties and the rights of the ACCC, because the ACCC can examine merger party executives on oath during the merger review process using compulsory powers. The ACCC also has full access to all evidence in the review process, including complainant witnesses, while merger parties will obtain only limited access to those submissions and data. Treasury intends to consult on procedural safeguards in 2024, but it is imperative that those safeguards include effective and practical ‘access to file’ provisions, permitting merger parties access to all of the evidence before the ACCC in complex merger reviews.

The role of the Federal Court will now be limited to judicial review of Tribunal decisions.

Authors

Tags

This publication is introductory in nature. Its content is current at the date of publication. It does not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. You should always obtain legal advice based on your specific circumstances before taking any action relating to matters covered by this publication. Some information may have been obtained from external sources, and we cannot guarantee the accuracy or currency of any such information.