The new Scams Prevention Framework: key considerations for regulated entities

21 February 2025

Federal Parliament recently passed legislation introducing a Scams Prevention Framework (SPF), as a new part of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth).

What you need to know

- Six overarching principles: governance, prevention, detection, reporting, disruption and responding to scams.

- Three initial sectors: banking, telecommunications, digital platforms.

- Multiple regulators: ACCC (general regulator and digital platforms), ASIC (banks) and ACMA (telcos).

- Tiered framework: SPF added to the Competition and Consumer Act, SPF rules and sector-specific codes to follow in subordinate legislation.

- No mandatory compensation to scam victims: However, there will be mandatory access to redress: internal dispute resolution and external dispute resolution (managed by ACFA). Scam victims can also initiate court action.

- Civil penalties: Tier 1 for contravention of prevent, detect, disrupt or respond principles; Tier 2 for contravention of report or govern principles or sector codes.

- Enactment date: 21 February 2025, following royal assent, however, regulated entities will not be subject to the SPF until their sector is designated, with the possibility of a transition period, depending on the designation instrument.

- What’s next: Government to commence drafting SPF rules and SPF codes for the three initial sectors, with mandatory consultation with industry.

What you need to do

Businesses within the initial sectors of banking, telecommunications, and digital platforms, and future sectors of superannuation, insurance, online marketplace and cryptocurrency, should take steps to prepare for the rollout of the SPF regime, including:

- engaging in consultations on the designation of regulated sectors and SPF codes, which will set out the mandatory compliance requirements and details on what scam controls and governance frameworks regulated entities will need to implement;

- designing and implementing (further) scams controls to prevent, detect, disrupt and report scams, as well as systems to gather scams data and scams intelligence;

- amending privacy policies and collection notices to include a purpose of preventing, detecting and responding to scams, so they can be implemented as soon as the applicable SPF code is published;

- reviewing and/or amending existing governance structures, responsibility frameworks, compliance controls and internal dispute processes to ensure they are fit to prevent, detect, disrupt and report scams and respond to complaints about scams; and

- reviewing and analysing historic complaints about scams connected to your business, if any.

What’s included in the Scams Prevention Framework?

New concepts

As defined in the SPF, a scam is a: “direct or indirect attempt (whether or not successful) to engage an SPF consumer of a regulated service where it would be reasonable to conclude that the attempt: (a) involves deception; and (b) would, if successful, cause loss or harm, including the obtaining of SPF personal information of, or a benefit (such as financial benefit) from, the SPF consumer or the SPF consumer’s associates”. The definition seeks to capture the wide range of activities scammers engage in and that may adapt and evolve over time.

A ‘SPF consumer’ includes a ‘natural person’ or a small business operator. The SPF has extraterritorial reach to ‘natural persons’ ordinarily resident in Australia and to entities providing services outside Australia where that entity is Australian resident or has a permanent establishment for income tax purposes.

Regulated sectors will initially be banking, telecommunications, digital platforms (social media, paid search engine advertising, and direct messaging), with superannuation, insurance, online marketplace and cryptocurrency industries on notice for future designation.

The SPF is grounded in six overarching principles with which regulated entities must comply:

- Govern: Entities must have comprehensive documented governance and oversight of scam performance.

- Prevent: Take reasonable steps to prevent scams, beyond merely acting on actionable scam intelligence.

- Detect: Take reasonable steps to detect scams as they occur or soon afterwards.

- Report: Entities must report actionable scam intelligence to the ACCC.

- Disrupt: Take reasonable, timely and proportionate steps to disrupt scams or prevent loss or harm arising from scams.

- Respond: React to scams by having accessible mechanisms for consumers to report scam activity and internally resolve disputes.

The considerations as to whether an entity has taken ‘reasonable steps’ include, whether the entity has complied with any corresponding SPF code obligations, the entity’s size, services, consumer base and scam risks.

A regulated entity will be provided ‘safe harbour’ (meaning that it will not be liable in civil proceedings) for taking action to disrupt scam activity for a maximum of 28 days from the date when intelligence becomes actionable scam intelligence, provided the entity acts in good faith, complies with the SPF, and takes steps that are reasonably proportionate and reversible.

A multi-regulator approach

The ACCC will be the general regulator and each regulated sector will have its own regulator: ASIC for banks; ACMA for telecommunication providers; and ACCC for digital platforms. If new sectors are designated, the ACCC will be the interim regulator until a sector regulator is designated. Sector regulators will be expected to enter arrangements to manage risks such as: unclear roles and responsibilities; inconsistent regulatory and enforcement approach; and duplication in regulatory or enforcement action.

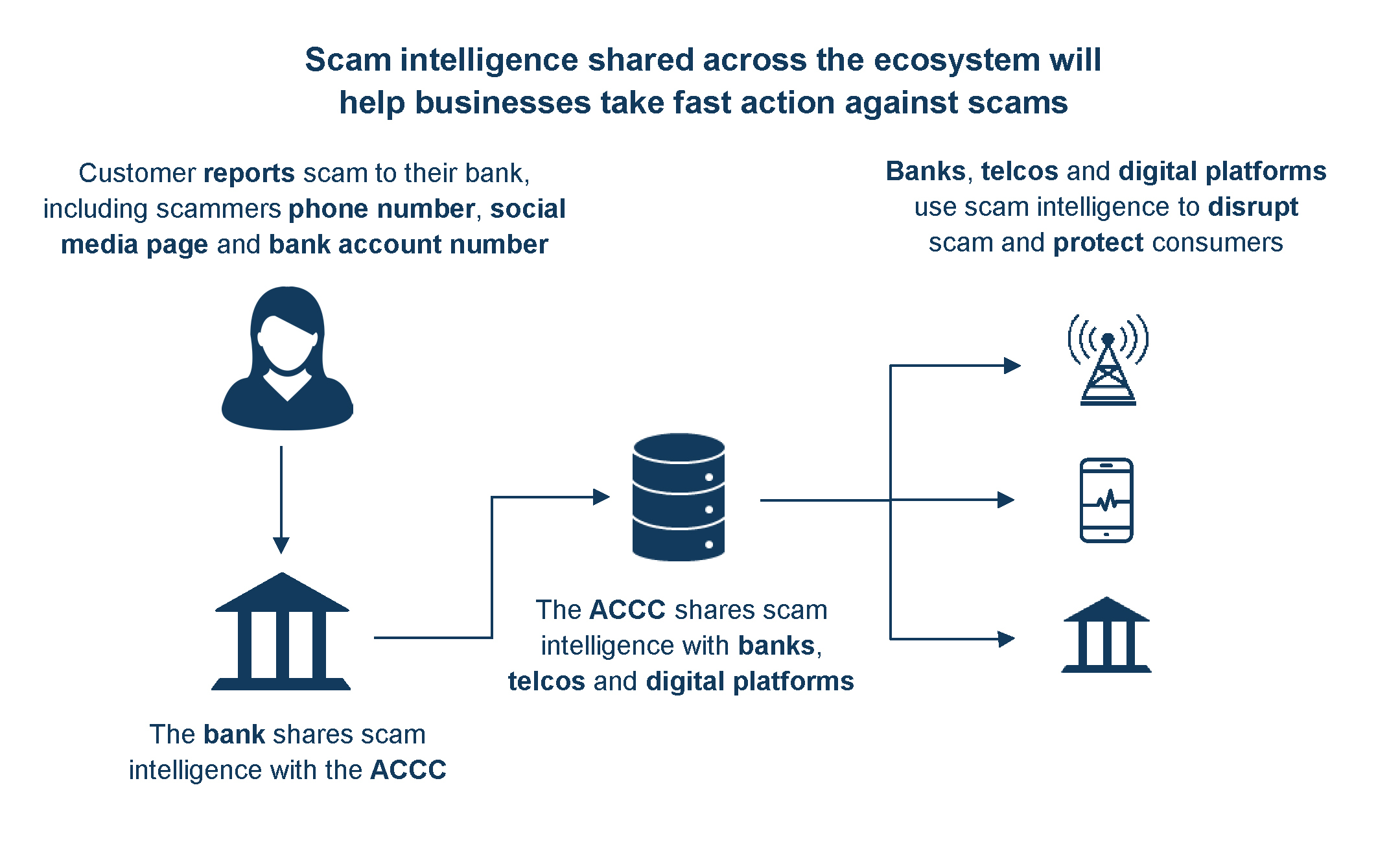

The regulators will be able to share information to support the administration or enforcement of the SPF (without being subject to notification requirements to affected persons). Treasury has indicated that regulated entities can also share information with the ACCC, which the ACCC can on-share with other regulated entities, as follows:

Civil penalties

The contraventions for the civil penalty provisions are two-tiered, reflecting that contraventions of some principles are likely to create greater harm to consumers, whereas other contraventions are more systems and process-focused.

| Contravention | Penalties |

|---|---|

Tier 1 Prevent, detect, disrupt or respond principles |

Entity: The greater of:

Individual: $2,636,700 |

Tier 2 Governance and report principles, or a SPF code |

Entity: The greater of:

Individual: $528,000 |

Regulators can seek multiple remedies for a single contravention by a regulated entity but cannot impose multiple civil penalties for the same contravention. Other remedies include injunctions, enforceable undertakings and statutory actions for damages.

Redress

The SPF does not mandate compensating victims of scams. It provides that regulated entities must have redress mechanisms available to consumers. These include internal (IDR) and external (EDR) dispute resolution mechanisms. There is also a route for a consumer to pursue court action.

The policy intention is that IDR complaints handling will be driven by a ‘no wrong door’ principle, meaning a consumer can complain to any regulated entity connected to the scam and the entity will need to cooperate with other entities involved to resolve the complaint in good faith. Where an entity is unable to resolve a complaint, consumers will have access to a single EDR body, AFCA.

Regulated entities will be required to give consumers a ‘statement of compliance’ when undertaking IDR. Such a statement will be admissible in EDR and may be used in any court proceedings. Provision of false or misleading information may be referred to the ACCC for investigation. If an entity indicates it has not complied with its SPF obligations in a statement, it is expected to compensate the consumer for any loss caused by the scam or justify the lack of compensation.

What’s not included?

Apportionment between regulated entities

At the court action stage, ‘concurrent wrongdoer’ provisions provide for apportioning liability based on what the court thinks justly reflects the responsibility the regulated entities involved. However, the SPF is silent on how liability will be apportioned at the IDR and EDR stages, aside from clarification (introduced when the Bill passed through the Senate) that guidelines for apportioning liability at IDR do not need to be consistent with the proportionate liability rules that apply in court actions for damages.

Follow-on class actions

It is not presently clear whether section 137H of the Competition and Consumer Act (which provides that findings and admissions made in any proceedings under the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) stand as prima facie evidence in other types of proceedings under the ACL) will apply to the SPF. It is possible that class action risk may arise either in this ‘follow-on’ context, piggybacking on regulatory action, or independently where a scam has sufficient reach to meet commercial thresholds of plaintiff law firms and funders.

Interface with AML/CTF regime

The interaction between the SPF and the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Act 2006 (Cth) (AML/CTF regime) is not explicitly addressed, including any details on facilitating effective collective scam prevention efforts and reducing the compliance burden or ‘double-handling’ of reporting obligations on regulated entities.

Recent reforms to the AML/CTF regime include provisions for regulations to be made that would allow intelligence sharing between banks. Such regulations have not yet been made, and will not address sharing of scams intelligence with telecommunication companies or tech platforms. Accordingly, unless further guidance is provided by AUSTRAC, banks will be left to determine what information they can share and whether any sharing is prejudicial to an investigation under the new AML/CTF regime.

Interface with Privacy regime

The inclusion of personal information in the definition of a scam overlaps with obligations under the Privacy Act 1998 (Cth) (and equivalent state regimes) regarding the handling of personal information (Privacy regime). The SPF is silent on this issue.

The updated Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights (contained within the Revised Explanatory Memorandum) acknowledges the issue and suggests that it does not raise privacy concerns, as entities that are expected to receive and disclose personal information under the SPF will generally be subject to Privacy regime obligations regarding handling personal information. To ensure ongoing privacy compliance, one of the steps that businesses should take is to review and update their privacy policies and collection notices to ensure that they address the collection, handling and disclosure of customers’ personal information to third parties to prevent, disrupt and respond to scams.

SPF rules and SPF codes

The SPF legislation as passed provides only the overarching framework, with operational detail to follow in subordinate legislation prescribing SPF rules and sector-specific SPF codes.

Sector codes for the three initial sectors are set to be developed through consultation with industry and consumers in 2025. Treasury has provided some examples of what obligations the codes may include:

- Banks: Implement technology to give customers greater confidence they are paying who they intended.

- Digital Platforms: Check all advertisers of financial products have an Australian Financial Services Licence.

- Telecommunications: Implement an anti-scam filter to block SMS messages with known phishing links.

Transition period

The SPF came into effect on 21 February 2025 following royal assent. However, regulated entities will not be subject to the SPF until their sector is designated by the Minister. Whether there will then be a transition period (for example, deferring the SPF coming into effect until the applicable SPF code is in force) will depend on the designating instrument.

This means that regulated entities may be required to comply with the SPF on short notice having little time to adjust their internal systems, policies and procedures. For example, regulated entities will need to proactively develop new reporting systems and processes so that once designated they will be in a position to report scams to the ACCC within 24 hours of becoming aware of a scam.

Further, regulated entities must receive certification of SPF compliance by a Senior Officer within 12 months of becoming a regulated entity and within seven days of that date annually thereafter.

Authors

Head of Intellectual Property

Partner

Partner

Partner

Special Counsel

Special Counsel

Lawyer

Tags

This publication is introductory in nature. Its content is current at the date of publication. It does not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. You should always obtain legal advice based on your specific circumstances before taking any action relating to matters covered by this publication. Some information may have been obtained from external sources, and we cannot guarantee the accuracy or currency of any such information.